The Anni Albers Retropsective

Anni Albers, Tate Modern, 11th October to 27th January 2019

I felt very lucky to have caught the retrospective of Anni Albers work during my trip to London. I have been a big fan of her work for decades. To follow is some of the highlights abstracted from the show and the accompanying texts.

The show was a huge celebration of Albers' dedication and pioneering work as an Artist, within the history of abstract modernism, and within a story of textile art. It also coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus.

For me, this exhibition highlighted Albers' compassion and concerns between commercial design and craftsmanship. It showed me some powerful links between creativity and production, and the exploration of innovative materials and her consistent development of new techniques.

I want to do my best to simply walk you through each room in the show (11 in total). This is by no means an essay on my part, but just an overview, a bit of background of what I loved and learnt.

Hope you enjoy.

The tactile room (photo from Dezeen article by Augusta Pownall, Nov 2018)

Room 1: Introduction to Albers (born Annelise Else Frieda Fleischmann, 1899-1994)

Anni Albers preference was to study painting at the Bauhaus, but her application was turned down.

Eventually she became a student at the Bauhaus in 1922, enrolling in weaving. Although, Initially reluctant to study weaving, as it was known as the ‘women’s department’, Albers soon took it, enjoying its complexities and challenges.

She said “threads caught my imagination” and “I have learnt to listen to threads and to speak their language. I learned the process of handling them”.

Albers was also a teacher. She produced two books. In 1959, she published a short anthology of essays titled ‘On Designing’, and in 1965 her influential book ‘On weaving’ was published. She wrote eloquently about the continued vitality of weaving, often in relation to its ancient past. She described weaving “as the adventure of being close to the stuff we are made of”

As we enter this first room, we are first greeted by her magnificent loom. In an essay by Sharon Tsang-De Lyster, she describes this as "her instrument, at the entrance. The rest of the displays proves the magic it is capable of making under Anni Albers’s hands: a rich collection of ‘pictorial weavings’, wall-hangings, and architectural fabrics" (https://www.thetextileatlas.com/craft-stories/anni-albers)

A Wall hanging, 1924, Cotton and silk, 168.3 x 100.3

Wall hanging 1927, Cotton and silk, 148 x 121.5

Both of these wall hangings are woven in very fine yarns of cotton and silk with a deceiving simplicity.

The original wall hanging, from 1927 is lost, and the one exhibited was rewoven by Gunta Stolzl in 1964. Gunta Stolzl also played a fundamental role in the development of the Bauhaus school's weaving workshop.

Room 2: Weaving at the Bauhaus

“One of the outstanding characteristics of the Bauhaus has been, to my mind, an unprejudiced attitude toward materials and their inherent capacities” Anni Albers

The Bauhaus art school in Weimar was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius, who wanted to create a school that brought together sculpture, painting, arts and crafts. Promoting all Arts as equal.

The weaving workshop enabled students to produce independent artistic works as well as designs for industrial manufacture, developing its own distinctive language which is evident in the works on display here.

This was was one of my favourite rooms in the show, I loved getting up close to these beautiful original Gauche studies for weavings.

Design for wall hanging 1926, (below) shows the three colours of thread to be used, red, black and white, and the pink and the grey occur through the combination of white warp and red or black weft.

Design for a wall hanging 1926, Gouache on paper, Albers.

Design for a silk tapestry 1925, watercolour and gouache on paper, Albers. 29.7 x 22.1

Design for a 1926 unexecuted wallhanging, Gouache with pencil on reprographic paper 38.4 x 25

Gunta Stolzl, (1897 – 1983) Design for a wall hanging 1927. Watercolour, pencil, ink and gouache.

Watercolour designs for weaving, Lena Meyer-Bergner (1906-1981)

Meyer – Bergner, was one of Albers fellow students in the Bauhaus weaving workshop and produced several designs for weavings. This example in watercolour on paper are designs for carpets.

Unidentified students, Bauhaus, fabric/weaving swatches

Black white and yellow (original 1926) Re-woven by Gunta Stolz in 1965. Cotton and Silk

Untitled 1941, Rayon, linen, cotton, wool and jute

Untitled 1941, Detail.

This work is thought to be one of the first weavings Albers produced as a pictorial form to be framed and displayed on a wall. In the process of weaving, Albers incorporated a wide edge of plain weave around the central grid, like a mount.

City, 1949, Linen and Cotton.

Detail - City, 1949, Linen and Cotton.

La Luz. Linen and metallic thread

In La Luz I, Anni Albers used linen and metal threads to create the impression of shifting light as well as texture. The cross shape seems to radiate light with the clever use of thicker and thinner threads.

When Hannes Meyer, the 2nd director of the Bauhaus, designed the ADGB trade Union School in Bernau near Berlin, he commissioned Anni Albers to design a wall covering for the auditorium. The black and white threads on the front were interwoven with transparent cellophane, which has a metallic appearance that reflected the artificial light in the windowless auditorium.

On the back of the weaving, Albers used chenille to produce a velvet-like surface that muffles sound. Albers received her Bauhaus diploma for this design in 1930. The architect Philip Johnson, who recommended her to Black Mountain College in the US, said this woven textile was her ‘passport to America’

Room 3: Black Mountain College

“I tried to put my students at the point zero. I tried to have them imagine, let’s say, that they are in a desert in Peru, no clothing, no nothing… So what do you do? You wear the skin of some kind of animal maybe to protect yourself from too much sun or maybe the wind occasionally. And you want a roof over something and so on. And how do you gradually come to realize what a textile can be? And we start at that point”

In 1933 the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close. Anni and her husband Josef Albers, were offered teaching positions at the Progressive art school, ‘Black Mountain College’ in North Carolina. Here Anni Albers encouraged her students to explore simple weaving patterns using found objects, and using simple back strap looms.

Study made with Corn Kernels. (This was one of 4 photographs on display others were studies using, twisted paper, grass, and metal shavings

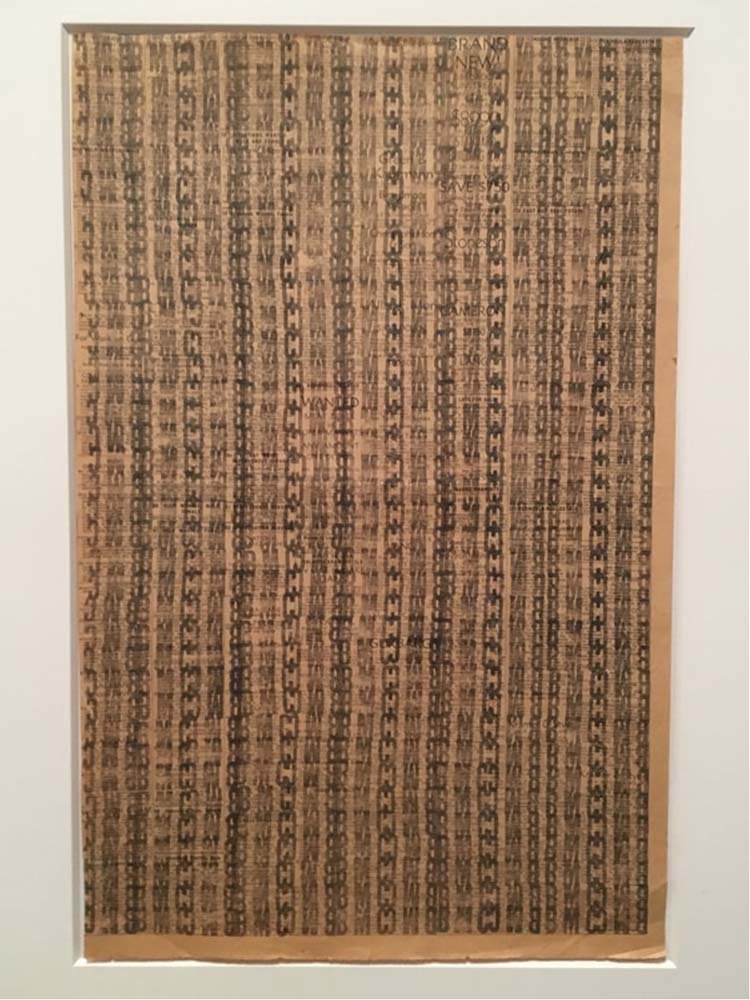

Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) BMC Stamp, 1950, ink on newsprint

Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) BMC Stamp, 1950, ink on newsprint

Ruth Asawa was one of Josef Albers’s students at Black Mountain College, and did these while on duty in the laundry room of the college, using stamps used to mark the laundry tickets. (I loved these!)

Room 4: Ancient Writing

“the textiles of ancient Peru are to my mind the most imaginative textile inventions in existence. Their language was textile and it was a most articulate language….it lasted until the conquest in the 16th century. Until that time, they had no written language, at least not in the sense we think of, as a form of writing’

This is something close to my heart, the relationship between text and textile. (and was the basis of my thesis for my M.A in the mid 90's, but don't get me started)

Anni Albers understood that pre-Columbian textiles served a communicative purpose, especially in ancient Peru, where there was no written language. As a young student in Berlin, Albers had regularly visited the Museum of Ethnology and its collection of Peruvian textile art.

The black and gold weaving she titled Ancient Writing was made the year after her visit to Mexico in 1935.

Ancient writing was the first in a series of pictorial weavings whose titles refer explicitly to texts and coded or ciphered character languages. Haiku 1961, Code 1962 and Epitaph 1968

Pictorial Weavings

Room 5: Pictorial Weavings

"To let threads be articulate again and find a form for themselves to no other end that their own orchestration, not to be sat on, walked on, only to be looked at, is the raison d’etre of my own pictorial weavings”.

Anni Albers distinguished between the textiles she designed for architecture or interiors, and her smaller ‘pictorial weavings’.

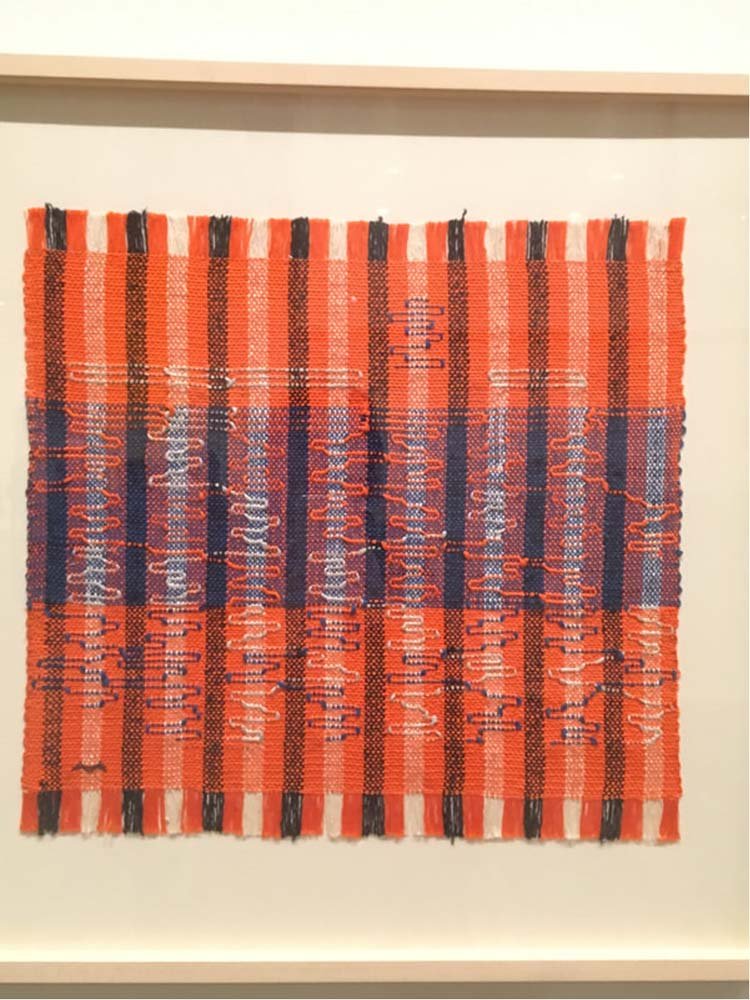

Albers made many of her pictorial weavings in the 1950’s and used a small handloom to create these pieces, several of which incorporate a technique known as leno or gauze weave, where the vertical warp threads twist over each other around the horizontal weft threads.

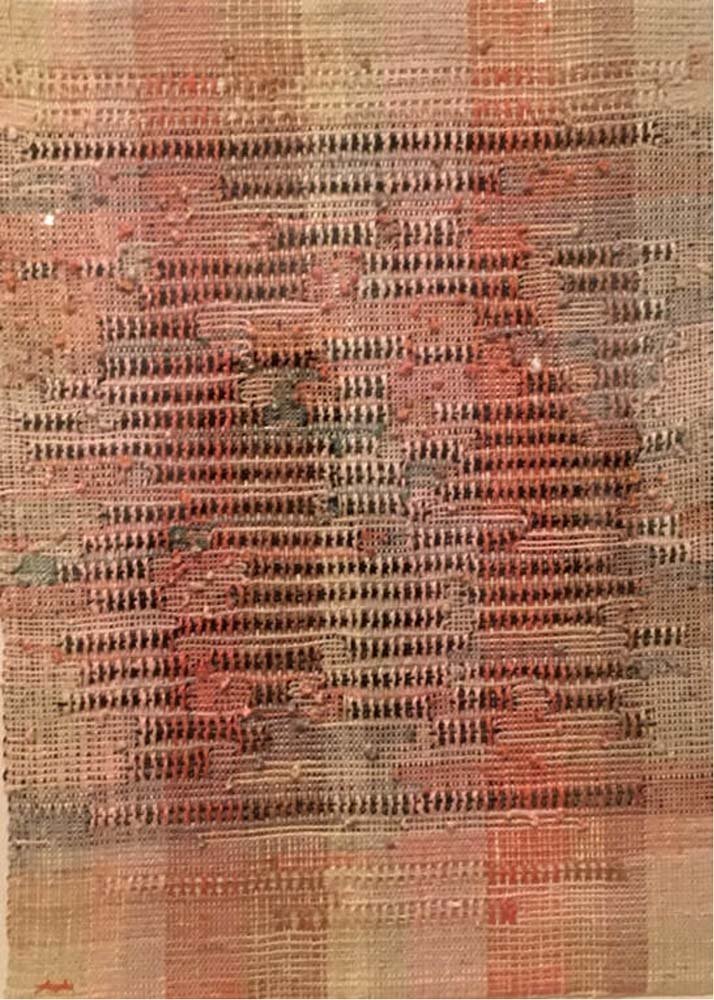

Development in Rose 1, 1952, Linen

Black-White-Gold 1, 1950, Cotton, Lurex and jute

Development in Rose 2, 1952, Linen

Development in Rose 2, 1952, Linen (Detail)

Play of Squares, 1955, Wool and Linen

Play of Squares, 1955, Wool and Linen (detail)

Northwesterly, 1957, Cotton, rayon and acrylic.

Northwesterly, 1957, Cotton, rayon and acrylic.

Variation of a theme. 1958, Cotton Linen and plastic

Variation of a theme. 1958, Cotton Linen and plastic. Detail

Dotted, 1959, wool

Albers employs another ancient technique in this pictorial weaving that gathers yarn in twists and knots to create bobbles across the surface of the work.

Dotted, 1959, wool

Dotted, 1959, wool (detailed)

Knoll.

In 1951, the architect and furniture designer, Florence Knoll, invited Albers to collaborate with the Knoll textile department, to produce new fabrics. Albers consulted on a number of innovative fabrics for the company over a 30 year period. She developed several open weave casement fabrics as covers for modernist glass windows. Loved seeing these.

Designs for Knoll

Designs for Knoll

Room 6: The Pliable Plane.

This room explored the relationship between textiles and architecture. Textiles, are so often an after-thought in a space! What if there was an understanding between the architect and the inventive weaver?

In her essay the ‘pliable plane’, Anni Albers explored the relationship between textiles and architecture, examining its early beginnings and proposing a future where textiles become integral to architectural design. She spoke of the varying opacities, tensions and light reflecting qualities textile panels and room dividers can bring into a space.

Albers worked on many architectural commissions, collaborating with modernist architects and designers.

In 1944 she designed a drapery fabric with light-reflecting qualities for the Rockefeller Guest House in Manhattan, New York.

Room 7: Six Prayers

Six prayers 1966-7, is Anni Albers most ambitious pictorial weaving. In 1965 she was commissioned by the Jewish Museum, New York, to create a memorial to the six million Jews who had been killed in the Holocaust.

Albers was from a Jewish family, though she had been baptised as a Protestant and saw herself as a Jewish only ‘in the Hitler sense’. Albers was undoubtedly intrigued by the commission. The six sombre, contemplative panels of Six prayers represent the six million Jews. Albers said of the work: ‘I used the threads themselves as a sculptor or painter uses his medium to produce a scriptural effect which would bring to mind sacred texts’

6 prayers, 1966-7, Cotton, Linen, bast and silver thread 186.1 x 297.2

Room 8: The event of a thread:

‘Weaving is an example of a craft which is many sided. Besides surface qualities, such as rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft, it also includes colour, and as the dominating element, texture…. like any craft, it may end in producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art’

Albers used a floating weft technique and brocade weaving (adding surface threads to a basic weave), and was able to integrate additional threads as free lines – ‘drawing’ with these threads into structure of her pictorial weavings.

In the mid-1940’s Albers began to explore knots and began to sketch and paint entangled, linear structures. Whether using paint, pencil or yarn, Albers’s works reflected her often quoted statement: ‘The thoughts….can, I believe, be traced back to the event of a thread’.

Intersecting, 1962, Cotton and Rayon 40 x 41.9

Intersecting, 1962, cotton and Rayon. (detail)

An Anni Albers rug from 1959. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Students at Black Mountain College weaving on backstrap looms, Black Mountain, NC, 1945. Photo: John Harvey Campbell. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Room 9: On Weaving

“one of the most ancient crafts, hand weaving is a method of forming a pliable plane of threads by interlacing them rectangularly. Invented in pre-ceramic age, it has remained essentially unchanged to this day. Even the final mechanisation of the craft through introduction of power machinery has not changed the basic principle of weaving”

This room demonstrates how extensively Anni Albers explored the theory and practice of weaving.

Much of the source material for her two influential books are shown in this room. (In 1959, ‘On Designing’, and in 1965 ‘On weaving’).

'On weaving' served as a kind of visual atlas, exploring the history of the last 4,000 years of weaving around the world, as well as examining technical aspects of the craft and the development of the loom.

This room contained many beautiful collections of textile artifacts from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. It also exhibited some of the work of artists such as Jean (Hans) Arp and Lenore Tawney, who were well known for fibre art in the 1960's. I have been a fan of Lenore's work, so it was very cool to see these drawings on display.

Lenore Tawney (1907 - 2007), That enters from the end into the beginning, 1964, Ink on Paper

Camino Real

The Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta invited Albers to produce a large wall hanging to hang in the bar of his new hotel in Mexico City called the Camino Real which opened in 1968. Other commissioned artists were included Alexander Calder and Mathias Goeritz. The arrangement of these small triangular units that then create larger ones are reminiscent of the textiles and Zapotec architecture that Albers had seen at Mitla, Mexico.

Study for Camino Real tapestry

Anni Albers's tapestry Camino Real in the Lobby Bar at Camino Real hotel (1968). © Armando Salas Portugal © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Armando Salas Portugal.

Room 10: Materials as metaphor: Prints, drawings and textile samples

“…circumstances held me to threads and they won me over. I learned to listen to them and to speak their language….And with the listening came gradually a longing for a freedom beyond their range and that led me to another medium, graphics. Threads were no longer as before three-dimensional, only their resemblance appeared drawn or printed on paper. What I learned in handling threads, I now used in the printing process.”

Weaving is a physically demanding process, and Albers took to printmaking in later years which still reflected her love for colour, texture and pattern using simple grids and rows of triangles.

Study for triangulated Intaglio III, 1976. Ink and pencil on graph paper

Study for DO II, 1973, Gouache on diazotype, photographic paper 42.9 x 37.8

Room 11: Tactile sensibility

“if a sculptor deals mainly with volume, an architect with space, a painter with colour, then a weaver deals primarily with tactile effects”

Though Anni Albers was in favour of modern design and production, she held a strong belief that technology increasingly dulls our awareness of the tactile, or haptic, as it replaces the need to make new things with our hands. Her essay “tactile sensibility’ begins: “all progress, so it seems is coupled to regression elsewhere. We have advanced in general for instance in regard to verbal articulation. But we certainly have grown increasingly insensitive in our perception by touch, the tactile sense…For too long we have made too little use of the medium of tactility.

This room had skeens of different yarns that Albers used in her weaving. We were encouraged to touch.

It also had her eight harness Structo Artcraft handloom exhibited here. And ending the show, is a wonderful film by Simon Baker, showing contemporary weaver Ismini Samanidou working at this loom during a residency at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Connecticut.

Summary

I visited this show three times. Ha! I know, could have gone more. This was possibly one of the most influential shows I could have seen.

I used to struggle with the term 'fibre artist' or even 'textile artist' for many years of my life. I'm not exactly sure why. Perhaps I have struggled with my personal insecurities of textile art being in my mind, a lower class of art. So to see this celebration of Anni Albers work at the Tate Modern, this beautiful modern aesthetic of threads, has inspired me so much. And at the heart of this, it reminds me of the centuries of making for necessity and beauty, across so many cultures and languages.